What is Jūjutsu?

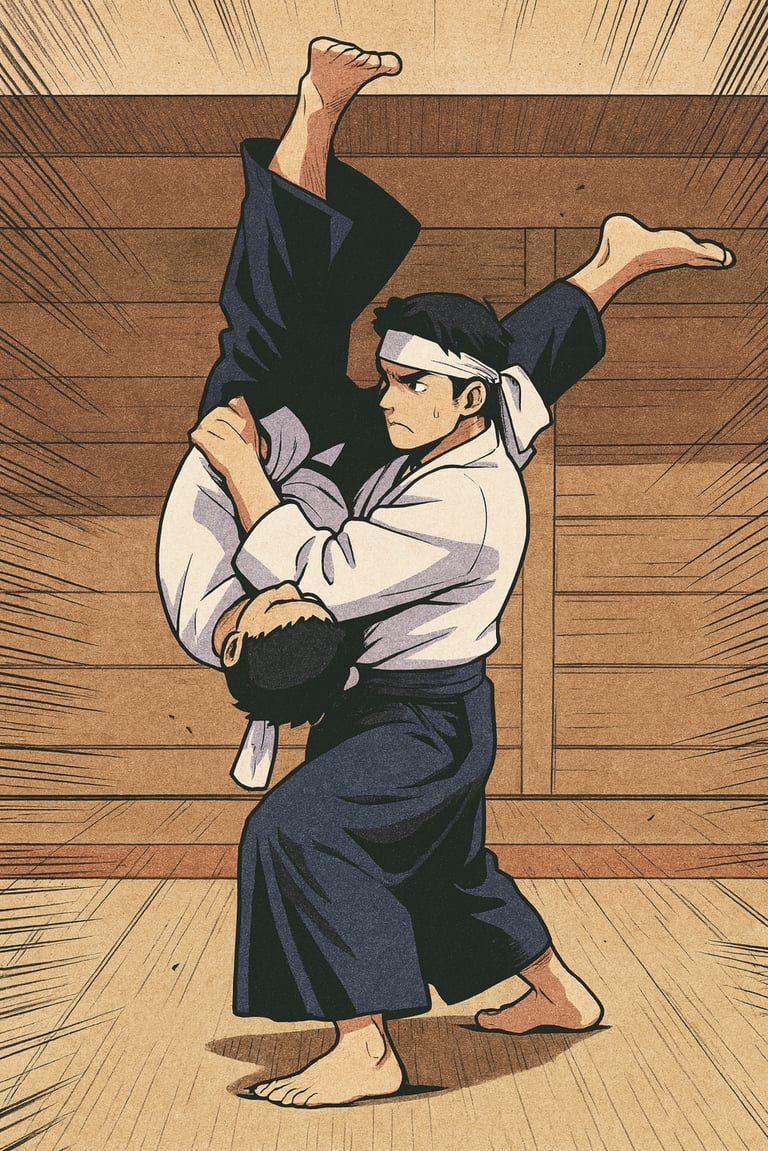

The Gentle Arts of Judo, Aikido, BJJ, and More

9/9/20254 min read

What Is Jūjutsu?

Jūjutsu (柔術) is one of Japan’s oldest and most influential martial traditions. The word is written with two characters: 柔 (jū) meaning “flexible, soft, yielding,” and 術 (jutsu) meaning “art, method, technique.” Put together, jūjutsu means “the art of yielding.”

In practice, jūjutsu is anything but soft in effect. It is a method of defeating an opponent through leverage, timing, and technique rather than brute strength. Classical jūjutsu systems (known as koryū) include:

Throws (nage-waza)

Joint locks (kansetsu-waza)

Chokes (shime-waza)

Pins and immobilizations

Atemi (strikes to vital points)

The “soft” or “yielding” part refers to the strategy — rather than clashing force against force, the practitioner redirects, blends, and overcomes strength through control.

Other Names for Jūjutsu in History

Depending on the school and era, jūjutsu has also been called by other names:

Yawara (和 or 柔): an older reading of the same character for “jū.”

Torite (捕手 / 取手): “seizing techniques,” often tied to policing and arresting methods.

Kogusoku (小具足): grappling methods while wearing light armor.

Taijutsu (体術): a broad term for “body techniques.”

Aiki-jūjutsu (合気柔術): schools emphasizing harmony (aiki) and blending.

These names reflect different emphases, but all describe variations of grappling and control within Japan’s martial culture.

Jūjutsu and Sumo: The Early Roots

Before the emergence of codified jūjutsu schools, Japan already had a tradition of grappling — Sumo (相撲). Early sumo, far older than Edo-period jūjutsu, was not the sport we see today but a ritual combat and wrestling system tied to Shintō ceremonies and courtly contests.

Many historians see Sumo as a precursor to jūjutsu. The ideas of unbalancing, clinching, and throwing an opponent influenced later battlefield grappling. Over time, as techniques spread among warriors, they evolved into specialized methods for fighting in armor, restraining enemies, or dueling — eventually formalized into the ryūha we now recognize as jūjutsu.

Jūjutsu in the Age of the Samurai

The Sengoku period (15th–16th centuries) was an age of near-constant war. Weapons dominated the battlefield, but grappling was vital when swords or spears could not be drawn or when fights collapsed into close quarters. Techniques known as yoroi kumiuchi (grappling in armor) emphasized leverage and control to unbalance or finish an armored enemy.

With the arrival of the Edo period (1603–1868) and peace under the Tokugawa shogunate, jūjutsu evolved. No longer needed primarily for battlefield killing, it developed into systems of self-defense, law enforcement, and formalized training. Hundreds of schools emerged, each preserving lineages of technique and strategy.

Influential Koryū Jūjutsu Schools

Some of the most important classical schools (koryū) include:

Takenouchi-ryū (founded 1532): Often considered the oldest surviving jūjutsu school, combining weapons, grappling, and restraining techniques.

Yagyū Shingan-ryū: A school with deep battlefield roots, known for its grappling, strikes, and unarmed combat against armored opponents.

Asayama Ichiden-ryū: Specialized in restraining and arresting methods (torite), influencing later aiki-based systems.

Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu: Preserved within the Takeda family, later taught publicly by Takeda Sōkaku. Famous for subtle principles of aiki (blending with intent) and the direct ancestor of Aikidō.

These ryūha weren’t just about fighting — they were complete systems that taught strategy, discipline, and the philosophy of the warrior’s way.

From Jūjutsu to Judo: The Koryū Legacy

By the late 19th century, Japan was modernizing. The samurai class was abolished, and martial training was no longer required for survival. Many jūjutsu ryūha declined, but some adapted.

Kanō Jigorō (1860–1938), a young scholar and martial artist, studied Tenshin Shin’yō-ryū and Kitō-ryū. From Tenshin Shin’yō-ryū he absorbed striking and immobilization techniques. From Kitō-ryū he learned throwing methods and the principle of kuzushi (breaking balance).

Kanō synthesized what he had learned into a new art: Jūdō (柔道, the “yielding way” often called “the gentle art”).

He emphasized randori (free sparring) alongside kata.

He removed the most dangerous techniques from sparring to make the practice safe.

He taught jūdō as a system for physical education, self-cultivation, and moral development.

In 1882, Kanō founded the Kōdōkan Jūdō Institute. What began as a streamlined version of classical jūjutsu became a global art — one that would influence self-defense, education, and sport around the world.

Modern Evolutions of Jūjutsu

Jūjutsu did not stop with Jūdō. Other evolutions spread worldwide:

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ): In the early 20th century, jūdō master Mitsuyo Maeda taught in Brazil. The Gracie family emphasized the ground fighting aspects of jūdō, eventually creating Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, today central in MMA.

Aikidō (合気道): Founded by Ueshiba Morihei, drawing heavily from Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu which itself has influences like Asayama Ichiden-ryū and Yagyū Shingan-ryū. Further, Ueshiba had also practiced Yagyū Shingan-ryū himself. He transformed combative jūjutsu techniques into a budō centered on harmony and reconciliation.

Hapkido (Korea): Influenced by Daitō-ryū through Choi Yong-sul, blending Japanese aiki principles with Korean striking traditions.

Aikidō as Jūjutsu — What’s Unique?

Aikidō is, in many ways, a modern form of jūjutsu. Its technical base is the same: joint locks, throws, pins, and strikes. What makes Aikidō unique is its purpose and philosophy:

Shared with jūjutsu: kata-geiko training, principles of leverage, blending, and control.

Unique to Aikidō: a commitment to non-destructive resolution. Instead of crippling or killing, Aikidō aims to neutralize without harm, expressing founder Ueshiba’s vision of peace and harmony.

Thus, Aikidō represents both continuity with the old and transformation into something new.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Jūjutsu

From the ritual contests of Sumo, to the battlefield grappling of armored warriors, to the refined kata of Edo-period ryūha, jūjutsu has always been about adaptability and control. Its legacy spread into Jūdō, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Aikidō, and even beyond Japan to arts like Hapkidō.

What unites them all is the central principle of jūjutsu: Strength yields to flexibility. Power bows to principle .

Today, whether on the mats of a jūdō dōjō, in a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu academy, or in the flowing practice of an Aikidō dojo, practitioners around the world are still exploring the timeless art of yielding.

If you've enjoyed this brief article, please check out the numerous other articles on our site. Feel free to contact us with ideas for other article that we should write about.

Calgary Rakushinkan

カルガリー楽心館

Experience traditional Japanese martial arts training.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

CONTACT

rakushincalgary@gmail.com

(403) 401-8257